It’s been a while since we’ve reviewed anything, so let’s talk about Silas Marner, shall we?

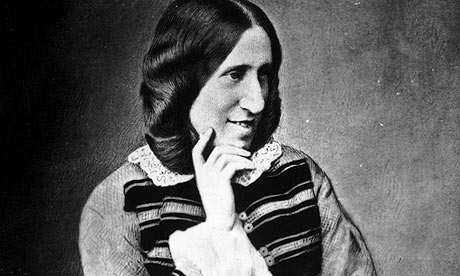

This book was my first experience with George Eliot, but Marner is certainly not her best known, or most highly acclaimed work. Still, I thought it would be a good way to edge myself closer to Middlemarch one day. Turns out it was a nice little read.

There’s a great use of dialect and colorful characters, and you can tell that Eliot had a blast recreating the quaint village life that serves as a backdrop for the story. In fact, the one criticism I’ll offer is that she got a little too carried away- relaying entire scenes that have nothing to do with what’s really going on. At certain points it occurred to me that a more appropriate title might have been “The Villagers of Raveloe… and Silas Marner,” but hey, who am I to complain? A story about a reclusive weaver? Catalepsy used as a plot device? Sold. Enough said.

Silas, the strange central character, is not at all likeable at first glance. But here’s what Eliot does so well: right off the bat, she gives us his backstory- a sad tale of betrayal and lost love that explains why he’s become the miserable misanthrope and village bogeyman that we meet in the first few pages of the book. You can’t help but cheer for the guy as things progress.

And progress they do. One reason I love to go back to the classics is that, for any of their other faults, they tend to be very well plotted. Things that occur in the opening chapters will come full-circle and be paid off in the end. In the case of Silas Marner, these twists and turns alternate between gut-wrenching losses and exhilarating stokes of luck. Ultimately, though, we’re given a happy ending, and Silas is utterly transformed by his character journey.

On top of all that, Eliot presents the reader with themes that are as relevant today as they were in her day. It’s a book about redemption, and community, and religion, and family. And if she wanders off on some tangents of “village color,” well, I think I can forgive that. Check it out.