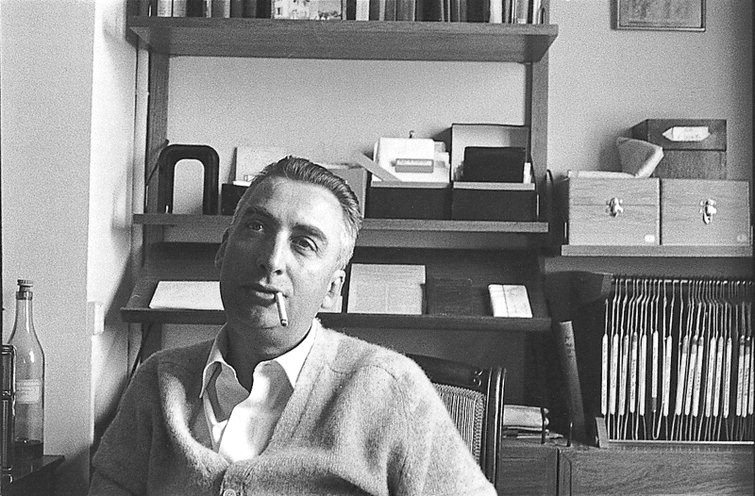

I gave pretty short shrift to Roland Barthes’ Mythologies when I “reviewed” it last year. But since the

Tour de France is kicking off tomorrow, I thought I’d share an excerpt from the

book on just that subject—to give you a taste for his analysis (with a few paragraph breaks inserted for readability):

“The Tour’s geography, too, is entirely subject to the epic necessity of ordeal. Elements and terrain are personified, for it is against them that man measures himself, and as in every epic it is important that the struggle should match equal measures: man is therefore naturalized; Nature, humanized.

"The gradients are wicked, reduced to difficult or deadly percentages, and the relays-each of which has the unity of a chapter in a novel (we are given, in effect, an epic duration, an additive sequence of absolute crises and not the dialectical progression of a single conflict, as in tragic duration)- the relays are above all physical characters, successive enemies, individualized by that combination of morphology and morality which defines an epic Nature. The relay is hairy, sticky, burnt out, bristling, etc., all adjectives which belong to an existential order of qualification and seek to indicate that the racer is at grips not with some natural difficulty but with a veritable theme of existence, a substantial theme in which he engages, by a single impulse, his perception and his judgement.”

“The dynamics of the Tour itself are obviously presented as a battle, but its confrontation being of a special kind, this battle is dramatic only by its décor or its marches, not strictly speaking by its shocks.

"Doubtless, the Tour is comparable to a modern army, defined by the importance of its materiel and the number of its servants; it knows murderous episodes, national funks, and the hero confronts his ordeal in a Cesarian state, close the divine calm familiar to Hugo’s Napolean (“Gem plunged clear-eyed into the dangerous descent above Monte Carlo”).

"Still, the very action of the conflict remains difficult to grasp and does not permit itself to be established in duration. As a matter of fact, the dynamics of the Tour knows only four movements: to lead, to follow, to escape, to collapse.

"To lead is the hardest action, but also the most useless; to lead is always to sacrifice oneself; it is pure heroism, destined to parade character much more than to assure results; in the Tour, panache does not pay directly, it is usually reduced by collective tactics. To follow, on the contrary, is always a little cowardly, a little treacherous, pertaining to an ambition unconcerned with honor: to follow to excess, with provocation, openly becomes a part of Evil (shame to the “wheel-suckers”).

"To escape is a poetic episode meant to illustrate a voluntary solitude, though on unlikely to be effective, for the racer is almost always caught up with, but glorious in porportion to the kind of useless honor which sustains it (solitary escapade of the Spaniard Alomar: withdrawal, hautiness, the hero’s Catilianism a la Motherlant). Collapse prefigures abandon, it is always horrible and saddens the public like a disaster. On Mount Ventoux, certain collapses have assumed a “Hiroshimatic” character. These four movements are obviously dramatized, cast into the emphatic vocabulary of the crisis; often it is one of them, in the form of an image, which gives its name to the relay, as to the chapter of the novel (Title: Kubler’s Tumultuous Grind). Language’s role is enormous here, it is language which gives the event- ineffable because ceaselessly dissolved into duration-the epic promotion which allows it to be solidified.”

—from Mythologies ,

by Roland Barthes