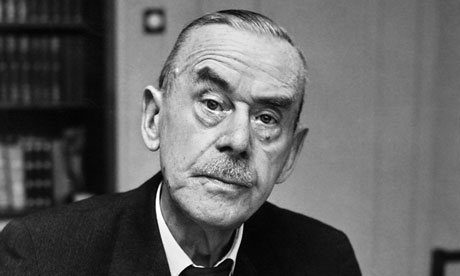

It’s been a couple months since I tackled Death in Venice & Other Tales by German author Thomas Mann. The collection was my very first introduction to Mann, and definitely won’t be my last.

Now, two months is enough time to make an honest-to-goodness review of the book a daunting task for my memory- but it’s also enough time to realize that this is a book that keeps coming back to me whether I mention it here or not. I’m tempted to use that well-worn reviewer’s cliché and call his stories ‘haunting.’

See, Mann has a real gift for creating pathetic, pitiable characters who are called upon by their author to respond to all sorts of inhumane cruelty and unrequited love. Whether sickly, deformed, corpulent or whatever, they all share the distinction of being irredeemable outcasts.

There’s “Little Herr Friedemann” who drowns himself in an ironic nod to Narcissus, by dunking his grotesque form in a reflecting pool. There’s the obese cuckold in “Little Lizzy” whose terrible shame only becomes obvious to him as he is forced to literally played it out on stage in a red silk baby dress. There’s the deeply wounded “Tobias Mindernickel” who takes out his worldly frustrations on his pet dog, eventually stabbing him to death. I could go on and on.

I’m not smart enough to namedrop philosophers, but Wikipedia tells me Mann is heavily influenced by Nietsche’s views on decay and the fundamental connection between sickness and torment and creativity. (Many of Mann’s characters are also artists or writers). Following this thematic thread from one story to the next, the reader gets the impression that, by the time we’ve come to the end, it is Mann that we have come to know- and not any of his pitiful characters.

Here’s an excerpt from his story “The Harsh Hour,” (which is essentially a story about writer’s block,) that gives us some insight into Thomas Mann’s own creative struggles:

“Talent itself, was it not pain? And when that thing there, that wretched work made him suffer, was that not as it should be? And almost a good sign? It had never gushed, and if it did so, that would truly arouse his disgust. It gushed only for dabblers and bunglers, for the quaint and the easily satisfied that did not live under the discipline of talent. For talent, ladies and gentlemen down there far away in the orchestra, talent is not facile, not frivolous. It’s not mere ability. At its root, it is a need, a critical knowing about the ideal, a dissatisfaction that cannot create or increase its powers without torment. And for the greatest, the most dissatisfied, their talent is their sharpest scourge.”

Another line from “Death in Venice” reveals the importance he places on solitude and isolation as an artist:

“Solitude ripens originality in us, bold and disconcerting beauty, poetry. But solitude also ripens the perverse, the assymetrical, the absurd, the forbidden.”

Of course, this last line also betrays the author’s closet homosexuality and foreshadows the forbidden lust that will keep his main character in a decaying city, at the mercy of a secret epidemic that will eventually take his life.

So maybe Nietsche was right. It doesn’t take a rocket surgeon to see that the pain and humiliation and anguish of Mann’s characters are a reflection of his own secret torment. But maybe that’s why it works so well. Give the Mann a whirl.