"From my apartment I would walk down the Calle de las Huertas, nodding to the street cleaners in their lime-green jumpsuits, cross El Paseo del Prado, enter the museum, which was only a couple of euros with my international student ID, and proceed directly to room 58, where I positioned myself in front of Roger Van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross .

"I was usually standing before the painting within

forty-five minutes of waking and so the hash and caffeine and sleep were still

competing in my system as I faced the nearly life-sized figures and awaited

equilibrium. Mary is forever falling to the ground in a faint; the blues of her

robes unsurpassed in Flemish painting. Her posture is almost an exact echo of

Jesus’s; Nicodemus and a helper hold his apparently weightless body in the air.

C. 1435; 220 X 262 cm. Oil on oak paneling.

"A turning point in my project: I arrived one morning at the

Van der Weyden to find someone had taken my place. He was standing exactly

where I normally stood and for a moment I was startled, as if beholding myself

beholding the painting, although he was thinner and darker than I. I waited for

him to move on, but he didn’t. I wondered if he had observed me in front of the Descent

and if he was now standing before it in the hope of seeing whatever it

was I must have seen. I was irritated and tried to find another canvas for my

morning ritual, but was too accustomed to the painting’s dimensions and blues

to accept a substitute. I was about to abandon room 58 when the man broke suddenly into tears, convulsively catching his breath. Was he, I wondered, just

facing the wall to hide his face as he dealt with whatever grief he’d brought

into the museum? Or was he having a profound

experience of art ?

"I had long worried that I was incapable of having a profound

experience of art and I had trouble believing that anyone had, at least anyone

I knew. I was intensely suspicious of people who claimed a poem or painting or

piece of music "changed their life," especially since I had often

known these people before and after their experience and could register no

change. Although I claimed to be a poet, although my supposed talent as a

writer had earned me my fellowship in Spain, I tended to find lines of poetry

beautiful only when I encountered them quoted in prose, in the essays my

professors had assigned in college, where the line breaks were replaced with

slashes, so that what was communicated was less a particular poem than the echo

of poetic possibility. Insofar as I was interested in the arts, I was

interested in the disconnect between my experience of actual artworks and the

claims made on their behalf; the closest I'd come to having a profound

experience of art was probably the experience of this distance, a profound

experience of the absence of profundity.

"Once the

man calmed down, which took at least two minutes, he wiped his face and blew

his nose with a handkerchief he then returned to his pocket. On entering room

57, which was empty except for a lanky and sleepy guard, the man walked

immediately up to the small votive image of Christ attributed to San Leocadio:

green tunic, red robes, expression of deep sorrow.

"I pretended to take in other paintings while looking sidelong

at the man as he considered the little canvas. For a long minute he was quiet

and then he again released a sob. This startled the guard into alertness and

our eyes met, mine saying that this had happened in the other gallery, the

guard's communicating his struggle to determine whether the man was

crazy—perhaps the kind of man who would damage a painting, spit on it or tear

it from the wall or scratch it with a key—or if the man was having a profound

experience of art. Out came the handkerchief and the man walked calmly into 56, stood before The Garden of Earthly Delights , considered it calmly, then totally lost his shit.

Now there were

three guards in the room—the lanky guard from 57, the short woman who always

guarded 56, and an older guard with improbably long silver hair who must have

heard the most recent outburst from the hall. The one or two other museum-goers

in 56 were deep in their audio tours and oblivious to the scene unfolding

before the Bosch.

"What is a museum guard

to do, I thought to myself; what, really, is a museum guard? On the one hand

you are a member of a security force charged with protecting priceless

materials from the crazed or kids or the slow erosive force of camera flashes;

on the other hand you are a dweller among supposed triumphs of the spirit and

if your position has any prestige it derives precisely from the belief that

such triumphs could legitimately move a man to tears. There was a certain

pathos in the indecision of the guards, guards who spend much of their lives in

front of timeless paintings but are only ever asked what time is it, when does

the museum close, dónde esta el baño. I could not share the man's rapture, if

that's what it was, but I found myself moved by the dilemma of the guards:

should they ask the man to step into the hall and attempt to ascertain his

mental state, no doubt ruining his profound experience, or should they risk

letting this potential lunatic loose among the treasures of their culture, no

doubt risking, among other things, their jobs? I found their mute performance

of these tensions more moving than any Pietá, Deposition, or Annunciation, and

I felt like one of their company as we trailed the man from gallery to gallery.

Maybe this man is an artist, I thought; what if he doesn't feel the transports

he performs, what if the scenes he produces are intended to force the

institution to face its contradiction in the person of these guards. I was

thinking something like this as the man concluded another fit of weeping and

headed calmly for the museum's main exit. The guards disbanded with, it seemed

to me, less relief than sadness, and I found myself following this man, this

great artist, out of the museum and into the preternaturally bright day."

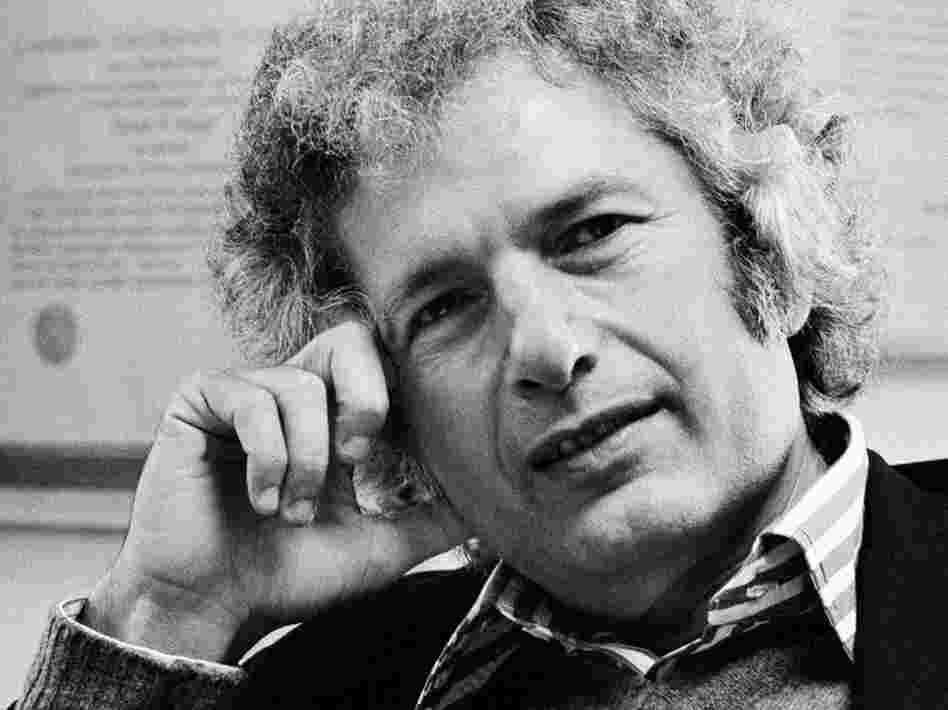

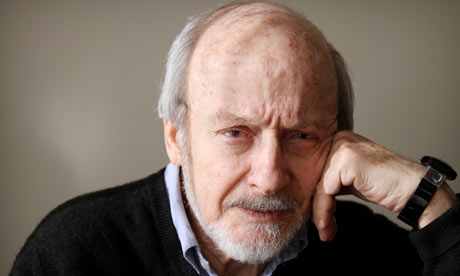

-From Ben Lerner's Leaving the Atocha Station