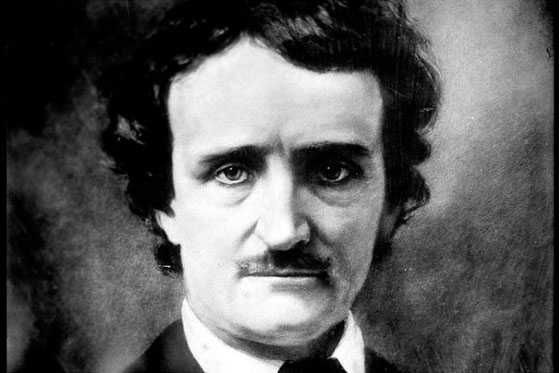

Edgar

Allen Poe only wrote one full-length novel. The modern reader may not hear much

about it anymore, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t plenty influential in its

day. Baudelaire translated it into French and riffed on it in some of his own

poetry. Jules Verne is said to have greatly admired the book, even penning what

can only be called a “fan-fiction” sequel called An Antarctic Mystery . Henry James alluded to the book in The Golden Bowl and Jorge Luis Borges praised it as Poe’s

greatest work. Moby Dick may have drawn pretty heavily on parts of it, and readers

of Life of Pi (or viewers of the gorgeous new movie by the

same name) may not even realize that the tiger’s name, Richard Parker, is an

homage to Poe’s only novel.

Having

said all that, I can’t remember a book I’ve read in the past couple years whose

ending was so unworthy of its beginning. In reality, it’s kind of impossible to

give Pym a fair reading in this day and age. In the

latter half of the book Poe was postulating about the completely unknown world

of the Antarctic- something even casual modern readers know quite a bit about

nowadays. For this reason, the whole last half of the book fell flat for me.

But the beginning was something else!

This

book started out promising intrigue and adventure, and did a great job

delivering on both counts. Our narrator is secreted away in the inaccessible lower

decks of a ship by his friend, the nephew of the captain. They agree that they

need to wait a certain period of time before exposing their stowaway plan, so

that it becomes impractical to turn back to port. But when the prearranged

period comes and goes with no word at all from the friend, Pym is left in his

stuffy hellhole of a hiding place, having exhausted his supplies of food or

drink and having no clue what’s going on above deck. As the narrator plays out

his mental and physical suffering, we’re treated to some classic Poe-ian angst,

every bit as good as the suffering in the “Tell-tale Heart.”

From

there the story leaps into a classic adventure tale, filled with mutiny, violent

sea storms, starvation, cannibalism and finally, rescue.

And

here’s where I wish I had put the book down. The survivors are rescued by a

boat en route to the Antarctic for the purpose of exploration. (Keep in mind,

no one knew of Antarctica when Poe put his story down on paper.) But what

follows is page after page of sleep-inducing, faux-scientific detail about the flora

and fauna on various islands in the southern seas. Seriously, by the time

you’ve used the word “declivity” for the sixth or seventh time, I think it’s

safe to say your story has come off the rails.

Their

discoveries include a black-skinned, black-teethed race of men, and some fifteen

foot long relative of the polar bear. The crew is eventually slaughtered by

this strange native people, all except for Pym and another man, who continue

south in a dinghy into mysterious, milky-white seas where a giant magical figure

appears out of nowhere and brings the book to a close.

Really,

that’s how it ends. I guess if I had picked up the book when it was published

in 1838, and the Antarctic region was still as unknown to Poe’s readers as some

distant planets are to us, it might have fared a little better in my judgment.

As it is, though, I can only say that Poe started out strong, then put me to

sleep, then woke me up and repeatedly jumped the proverbial shark.