Showing posts with label E.M. Forster. Show all posts

Showing posts with label E.M. Forster. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

Author Look-Alikes Vol. 8

Though

they don’t share the same hairline, there’s something in the eyes and mouth

that makes young Erich Maria Remarque look an awful lot like John Malkovich:

High

foreheard, low eyebrows, and piercing eyes- Jules Verne was his generation's Russel Crowe - plus a couple months of beard growth:

He's portly,

he's got a sly expression and lots of thick hair- you can almost picture Alexandre

Dumas walking into his local basement-level watering hole to a merry chorus of “Norm!”:

James

Fenimore Cooper kind of reminds me of the backstabbing friend from Ghost (Tony Goldwyn):

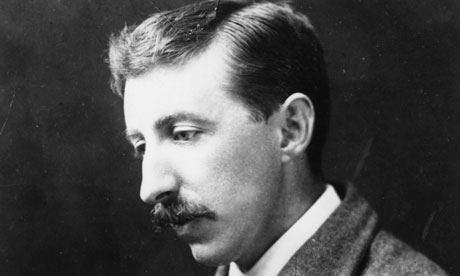

And

E.M. Forster? The first person who comes to mind when I look at that dude is

Macy’s smarmy in-house psychologist from “Miracle on 34th Street” (Porter

Hall):

Kind of makes you want to rap him on the head with your cane, doesn't it?

Labels:

Alexandre Dumas,

Author Look-Alikes,

E.M. Forster,

Erich Maria Remarque,

James Fenimore Cooper,

Jules Verne

Thursday, April 19, 2012

Review: A Room With A View, by E.M. Forster

There

are some among our readership who really have it in for E.M. Forster (what

gives?), but we hope you’ll bear with us as we review that author’s A Room With A View.

The

book was my first introduction to Forster, and I have to say that I came away

generally pleased. It’s not a read that will keep you on the edge of your seat-

its major plot points are conversations, betrayals of confidence, and rumors about

who will rent the vacant cottage at such and such a place. But if it won’t keep

you on the edge of your seat, I think there’s enough to keep you in your seat- to keep you reading right

to the very end.

Now,

it is at its core, a romance. This means that the story is wholly dependent on

a simple misunderstanding between the two principle characters stretching the entire

length of the book. If George an Lucy were able at any moment to actually sit

down and have a half-way decent conversation, there would be no story. But true

to form, they aren’t; and so there is. Fine.

But

here’s where Forster really whimps out: The tension builds and builds (Will

Lucy end her engagement to Cecil? Is George’s father really a murderer? Did

George not only steal a kiss, but blabber about it to a popular novelist?) We

anxiously await the moment when George and Lucy do finally hash things out, when she realizes that she loves him

and always has- but just at the crucial moment- Forster fumbles the ball! He hits

the fast forward button and next thing you know, George and Lucy are back in

Florence, reminiscing about the winding road that brought them back there. No

catharsis, just a few loose ends tied up after the fact. It’s as if he thought that scene

would be really difficult to write, so he played it out off-stage. It was a bit

of a disappointment.

Still,

there is a lot of beautiful writing, some great characters and nice settings. And he presents enough interesting

insights into love and happiness and religion to have earned a second read from

me. So, for the Forster fans out there: where should I go next? Howard’s End? Or A Passage To India?

Thursday, April 12, 2012

From the Pen of E.M. Forster

I

was just getting ready to type up a short review of E.M. Forster’s A Room With a View, when I stumbled upon

these excerpts I had highlighted during my read. I love how Forster gives life

to inanimate objects (his face “sprang into tenderness” or “battalions of black

pines witnessed the change”) and just as easily turns human characters into inanimate

works of art (“She saw him once again at Rome, on the ceiling of the Sistine

Chapel…”).

But

I think my favorite passage is the third one below. It also happens to be the central plot point of the book. The

image of violets running like liquid color is something that has stayed with me

since I finished the book last fall. It’s beautiful stuff. All emphasis below

is mine- they’re just the lines that knocked me senseless.

She watched the singular creature pace up and down the chapel. For a young man his face was rugged, and--until the shadows fell upon it--hard. Enshadowed, it sprang into tenderness. She saw him once again at Rome, on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, carrying a burden of acorns. Healthy and muscular, he yet gave her the feeling of greyness, of tragedy that might only find solution in the night. The feeling soon passed; it was unlike her to have entertained anything so subtle. Born of silence and of unknown emotion, it passed when Mr. Emerson returned, and she could re-enter the world of rapid talk, which was alone familiar to her.

She could not complete it, and looked out absently upon Italy in the wet. The whole life of the South was disorganized and the most graceful nation in Europe had turned into formless lumps of clothes. The street and the river were dirty yellow, the bridge was dirty gray, and the hills were dirty purple.

Light and beauty enveloped her. She had fallen onto a little open terrace, which was covered with violets from end to end. From her feet the ground sloped sharply into view and violets ran down in rivulets and streams and cataracts, irrigating the hillside with blue, heading round the tree stems, collecting into pools in the hollows, covering the grass with spots of azure foam. But never again were they in such profusion. This terrace was the well-head, the primal source whence beauty gushed out to water the earth. Standing at its brink like a swimmer who prepares, was the “good man.” But he was not the good man she had expected, and he was alone. George had turned at the sound of her arrival. For a moment he contemplated her as one who had fallen out of heaven. He saw a radiant joy in her face. He saw the flowers beat against her dress in blue waves. The bushes above them closed. He stepped quickly forward and kissed her.

In the Weald, autumn approached, breaking up the green monotony of summer, touching the parks with the gray-blue of mist, the beech trees with russet, the oak trees with gold. Up on the heights battalions of black pines witnessed the change, themselves unchangeable. Either country was spanned by a cloudless sky and in either arose the tinkle of church bells.

Lucy’s Sabbath was generally of this amphibious nature. She kept it without hypocrisy in the morning, and broke it without reluctance in the afternoon.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)