I

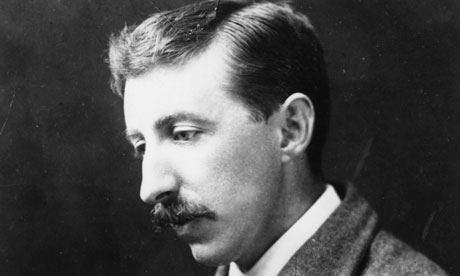

was just getting ready to type up a short review of E.M. Forster’s A Room With a View, when I stumbled upon

these excerpts I had highlighted during my read. I love how Forster gives life

to inanimate objects (his face “sprang into tenderness” or “battalions of black

pines witnessed the change”) and just as easily turns human characters into inanimate

works of art (“She saw him once again at Rome, on the ceiling of the Sistine

Chapel…”).

But

I think my favorite passage is the third one below. It also happens to be the central plot point of the book. The

image of violets running like liquid color is something that has stayed with me

since I finished the book last fall. It’s beautiful stuff. All emphasis below

is mine- they’re just the lines that knocked me senseless.

She watched the singular creature pace up and down the chapel. For a young man his face was rugged, and--until the shadows fell upon it--hard. Enshadowed, it sprang into tenderness. She saw him once again at Rome, on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, carrying a burden of acorns. Healthy and muscular, he yet gave her the feeling of greyness, of tragedy that might only find solution in the night. The feeling soon passed; it was unlike her to have entertained anything so subtle. Born of silence and of unknown emotion, it passed when Mr. Emerson returned, and she could re-enter the world of rapid talk, which was alone familiar to her.

She could not complete it, and looked out absently upon Italy in the wet. The whole life of the South was disorganized and the most graceful nation in Europe had turned into formless lumps of clothes. The street and the river were dirty yellow, the bridge was dirty gray, and the hills were dirty purple.

Light and beauty enveloped her. She had fallen onto a little open terrace, which was covered with violets from end to end. From her feet the ground sloped sharply into view and violets ran down in rivulets and streams and cataracts, irrigating the hillside with blue, heading round the tree stems, collecting into pools in the hollows, covering the grass with spots of azure foam. But never again were they in such profusion. This terrace was the well-head, the primal source whence beauty gushed out to water the earth. Standing at its brink like a swimmer who prepares, was the “good man.” But he was not the good man she had expected, and he was alone. George had turned at the sound of her arrival. For a moment he contemplated her as one who had fallen out of heaven. He saw a radiant joy in her face. He saw the flowers beat against her dress in blue waves. The bushes above them closed. He stepped quickly forward and kissed her.

In the Weald, autumn approached, breaking up the green monotony of summer, touching the parks with the gray-blue of mist, the beech trees with russet, the oak trees with gold. Up on the heights battalions of black pines witnessed the change, themselves unchangeable. Either country was spanned by a cloudless sky and in either arose the tinkle of church bells.

Lucy’s Sabbath was generally of this amphibious nature. She kept it without hypocrisy in the morning, and broke it without reluctance in the afternoon.