Well, as far as I can tell this is only a

concept put together to sell the digital track, so you can’t get in there and

play it like you could with this game. Still, it’ll be worth a couple minutes

to the Downton Abbey fans out there:

Friday, February 1, 2013

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Eudora Welty: Songwriter

Paul

Simon scored a worldwide hit with his 1986 album Graceland , winning the Grammy for Album of the Year in 1987. The

title track from that album, and the song that Simon has called the best he’s

ever written, also won Best Record of the Year in 1988. He did it by

collaborating with musicians and songwriters from all over the place: African

musicians like the Boyoyo Boys, Juluka and Ladysmith Black Mombazo, as well as

the Everly Brothers, Linda Ronstadt and Los Lobos closer to home.

And

while the music on the album is a mash-up of different styles (World-beat,

Zydeco, rock, a cappella, etc.) the lyrics are generally Simon’s own- with one

exception I uncovered recently. Here’s how Simon begins the title track, “Graceland:”

“The Mississippi Delta was shining like a national guitar”

Great

imagery, right? Now here is a passage describing a train ride through the Mississippi

Delta from Eudora Welty’s 1946 novel Delta

Wedding :

“The land was perfectly flat and level but it shimmered like the wing of a lighted dragon fly. It seemed strummed, as though it were an instrument and something had touched it.”

Ms.

Welty is not credited on the album, but we were

able to dig up the intriguing jam-session

photograph you see above. It’s interesting that she was not asked to add her

own vocal skills to the final cut of the record.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

What Bugs Me Wednesday: The War on Style

Elmore Leonard: "My most important rule is one that sums up the 10: if it sounds like writing, I rewrite it."

Jonathan Franzen: "Interesting verbs are seldom very interesting."

Esther Freud: "Cut out the metaphors and similes."

David Hare: "Style is the art of getting yourself out of the way, not putting yourself in it."

Stephen King: "The road to hell is paved with adjectives"

You know what really bugs me? The War on Style.

Look, I get these arguments. I really do. Yesterday’s post was all about simplicity. I get as bothered as the next guy by purple, florid prose (see the Henry James passage in this post for an example. Shudder.) But when was it decided that every great piece of fiction has to read like a USA Today article? I mean, come on, if the whole point of great writing is for the writer to take themselves out of the final product, then why am I reading these authors in the first place? Why not spend my time reading the hundreds of thousands of computer-generated books out there instead? I guess I’m in the camp that says the author should bring more to the table than a compelling plot line.

Look, I get these arguments. I really do. Yesterday’s post was all about simplicity. I get as bothered as the next guy by purple, florid prose (see the Henry James passage in this post for an example. Shudder.) But when was it decided that every great piece of fiction has to read like a USA Today article? I mean, come on, if the whole point of great writing is for the writer to take themselves out of the final product, then why am I reading these authors in the first place? Why not spend my time reading the hundreds of thousands of computer-generated books out there instead? I guess I’m in the camp that says the author should bring more to the table than a compelling plot line.

Let’s

look at the world of painting for an example. Can you imagine if visual artists

followed an Elmore Leonard-like rule that “if it looks like painting, I repaint

it?” Every art museum on earth would be chock-full of realistic, tromp l’oeil

paintings that look little different from photographs. That’s cool, I guess…

for a while anyway.

But sometimes you get tired of admiring technical skill. Sometimes you want to see the artist’s imagination at work, you want to see their innermost feelings splayed across the canvas. You want to see things in a way you never could have imagined them yourself. In short, you want to see some style.

But sometimes you get tired of admiring technical skill. Sometimes you want to see the artist’s imagination at work, you want to see their innermost feelings splayed across the canvas. You want to see things in a way you never could have imagined them yourself. In short, you want to see some style.

Here are some visuals to help you see what I'm talking about. What

if I mentioned the names Picasso, Dali, Monet, Matisse and Van Gogh, and the

only styles of painting that came to mind were the ones on the left below?

Picasso, before and after:

Dali, before and after:

Monet, before and after:

Matisse, before and after:

Van Gogh, before and after:

I

won’t call any of those early, left-side paintings bad or boring. I'd give my proverbial left-nut to be able to paint like that. But isn’t the world a little

richer because those same artists moved on from the technical proficiency displayed

on the left to blaze the new schools of painting displayed on the right? Isn't it great that they made it okay for others like Chagall or Lichtenstein or Warhol to bypass a realistic, technically proficient phase, and head straight for their own revolution of artistic styles?

Cubism, Surrealism, and Impressionism may not be your cup of tea, but there's no denying they exhibit an entirely different pull on the human spirit than paintings done in a photographic mimicry of real-world images can. Style matters. And the fact that styles differ, matters.

So back to literature. You want to pass out writing advice? Great. The more the merrier. But let's not pretend we're not losing something significant when the drumbeat to eliminate all adverbs, adjectives, metaphors, similes and complex verbs crowds out those who were born to take a slightly (or vastly) different path. Those parts of speech may just be the otherworldly color and heavy brushstrokes that will define a new kind of literature.

Cubism, Surrealism, and Impressionism may not be your cup of tea, but there's no denying they exhibit an entirely different pull on the human spirit than paintings done in a photographic mimicry of real-world images can. Style matters. And the fact that styles differ, matters.

So back to literature. You want to pass out writing advice? Great. The more the merrier. But let's not pretend we're not losing something significant when the drumbeat to eliminate all adverbs, adjectives, metaphors, similes and complex verbs crowds out those who were born to take a slightly (or vastly) different path. Those parts of speech may just be the otherworldly color and heavy brushstrokes that will define a new kind of literature.

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Le Mot Juste- Without a Thesaurus

In

A Moveable Feast Hemingway calls Ezra Pound:

“the man I liked and trusted the most as a critic then, the man who believed in the mot juste- the one and only correct word to use…”

Like Flaubert, Hemingway was known to be a believer in the ‘exact, right word’ and is

widely admired for his ability to cut to the chase and deliver a punch in just

a few, well-chosen words.

Yesterday’spost mentioning In Our Time jogged my memory about one of my formative “mot

juste” reading experiences. It happened while I was reading the short story “Big Two-Hearted River” in

that early collection of Hemingway’s, and it consisted of one simple sentence.

If you’ve read that two-part short story, you know it’s light

on plot, but heavy on description. In minute detail, we follow the character of

Nick Adams heading out, alone, on a fishing trip. Though it’s not explicitly

stated, the story’s got a lot to do with coming home from war and the regenerative

powers of nature. But in the midst of his lengthy descriptions of the trout

visible in the clear water of the river, Hemingway delivers this short

paragraph:

“His heart tightened as the trout moved. He felt all the old feeling.”

For

whatever reason, that last line absolutely knocked me on my tookus. To the point that I

still remember it ten years later. Hemingway didn’t even have to tell us what

the feeling was (Did Nick feel jittery? Serene? Ecstatic? Sentimental? Enthralled?

In his element? Happy? What?!) He didn’t have to scour the thesaurus for just

the right phrasing or color. What was it Nick felt? The old feeling! All of it. Nothing more.

How

incredibly plain and simple that is, but how effective it is in showing us that

this renewed connection with nature is rejuvenating and invigorating and

relaxing and a hundred other things, too. It doesn’t matter what the feeling

was, what matters is the effect it had on the character. And that’s what makes

it exactly the right word to use. I'm in awe of that kind of finesse.

Monday, January 28, 2013

Hemingwood Anderson

In this post we mentioned Sherwood Anderson’s influence

on the generation of writers that followed him and that came to dominate the 20th

century literary landscape. But it’s one thing to talk about influence, and

another thing altogether to see it plain on the page. Take a look at this passage

from Winesburg, Ohio , and tell me

you don’t see the pared down language and short-sentence-style that is so commonly

attributed to Ernest Hemingway.

"The story of Doctor Reefy and his courtship of the tall girl who became his wife and left her money to him is a very curious story. It is delicious, like the twisted little apples that grow in the orchards of Winesburg. In the fall one walks in the orchards and the ground is hard with frost underfoot. The apples have been taken from the trees by the pickers. They have been put in barrels and shipped to the cities where they will be eaten in apartments that are filled with books, magazines, furniture, and people. On the trees are only a few gnarled apples that the pickers have rejected. They look like the knuckles of Doctor Reefy’s hands. One nibbles at them and they are delicious. Into a little round place at the side of the apple has been gathered all of its sweetness. One runs from tree to tree over the frosted ground picking the gnarled, twisted apples and filling his pockets with them. Only the few know the sweetness of the twisted apples."

It’s amazing, isn’t it? I mean, that paragraph could be

something right out of In Our Time.

Friday, January 25, 2013

The Writer's Voice: Bill "Pappy" Faulkner

Few literary voices are as hard for me to reconcile with the

author’s actual speaking voice as William Faulkner’s.

How could the man who penned lines

like these, sound like a character right out of the Andy Griffith show? His

readers may call him William, and his friends may have called him Bill, but

after listening to that folksy, high-pitched twang, I feel like we should all just call him “Pappy.”

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Mini Reviews: Pressfield, Barthes and Boyle

Here are some more quick-hit reviews to bring me up to date

on my recent reading:

The

War of Art , by Steven Pressfield

This is a book for anyone who wants to create something

great, or accomplish some secret dream, and has had trouble getting started. “There's

a secret that real writers know that wannabe writers don't and the secret is

this: it's not the writing part that's hard. What's hard is sitting down to

write. What keeps us from sitting down is Resistance.” He does a great job of

naming the condition, and of helping you identify it in your life. And while I

really liked this book as I read it, as I look back after a month or two, I’m

hardpressed to remember what it was exactly that I’m supposed to do about it.

This could just be a fault of mine, but maybe the solutions he provides aren’t

as earth-shattering as the first read led me to believe. I guess I’ll have to

take a second pass through it to make sure I didn’t just fall asleep at the

wheel. But the good news is that it’s a book that would only take a couple

hours to read in the first place. I liked it as a breazy, but well-written,

get-your-butt-in-gear book, but it has yet to change my life so I’m going to

withhold judgement.

Mythologies , by Roland Barthes

This one was at times fascinating, but at other times

bordered on boring and arcane. Barthes is on a mission to uncover the real

meanings behind various pop culture phenomena that interested him in the France

of the mid 1950s. He might deconstruct the Tour de France, analyze a Marlon

Brando movie, pick apart a French governmental policy, explain a recent court

case or take a deep look at celebrity marriages. In some sections I found

myself saying, “Yes, exactly! Why haven’t I ever seen it that way before.” Take

this post I wrote after reading his thoughts on professional wrestling, for

example. But on other topics, I found myself shrugging my shoulders and

wondering, “Who really cares?” I imagine I would have enjoyed the book a lot

more if Barthes and I shared the same cultural milieu, or if he was still

around to turn his attention towards the

American culture of our day. But even so, when he wanders into semiology in the

second part of the book (in essence, the explanation of his explanations) I

quickly lost interest. It’s a pretty interesting literary touchpoint to have,

though, so I’m glad that I read it. And I’ll admit that some parts were

laugh-out-loud funny.

When

the Killing’s Done , by T. Coraghessan

Boyle

Before picking up this book, I had only read two stories by

Boyle, “The Lie” and “ Rapture of the Deep,” both of which were excellent, and

neither of which I can find for free online. So no links, sorry. I was excited

to see what Boyle can do in long form. And while I can’t say the subject matter

of this book was especially gripping (a battle over eradicating invasive

species on the channel islands of California) it really is masterfully written

and it will transport you into the clashing worlds of both environmental

activists and government-employed ecologists. In doing so, Boyle does something

pretty amazing: he makes you care almost equally about the protagonist and the

antagonist, as he unveils the background experiences and rationale that drives

each of them toward collision. I think the narrow focus of the themes keeps it

from being a great, universally appealing book, but it’s certainly a good one.

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

The Real Winesburg, Ohio

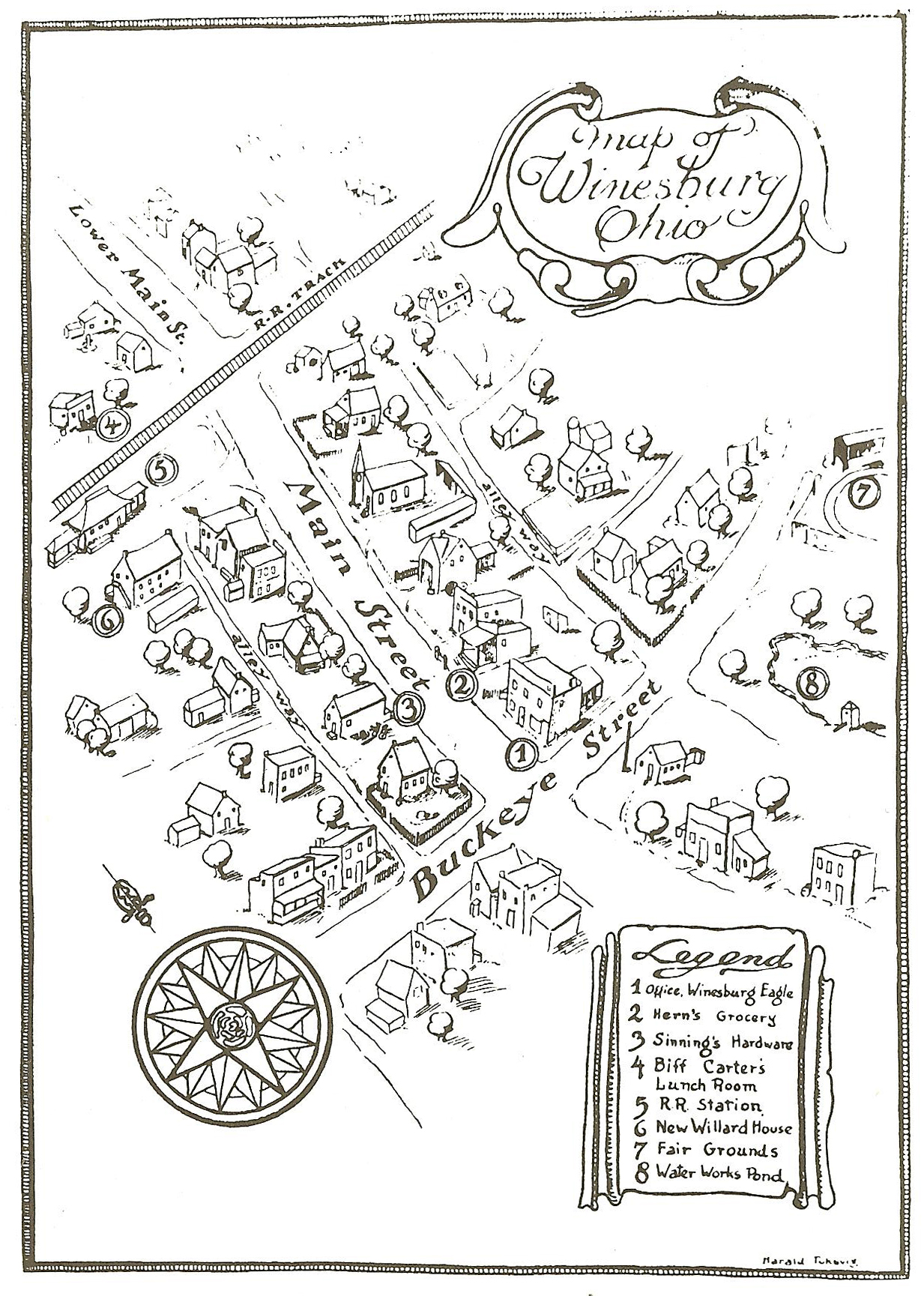

Immediately

upon opening the book, readers of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio are greeted

by a hand-drawn map of the fictional town that is the novel’s setting:

Turns

out Winesburg was a thinly veiled representation of Anderson’s own hometown of Clyde,

Ohio which, like its fictional counterpart, has a Main Street that crosses Buckeye

Street and some railroad tracks a little further north. If you’ve read this post

or this post, you know where I’m going with this. Here is what Clyde, OH looks

like today:

The

distances in the map of Winesburg are deceptively short (a half dozen

structures fill the stretch between Buckeye and the Train tracks, a span that

reaches a 1000 feet in the real world) and there’s not much in terms of

landmarks that would jump out and link the two maps. Not even the train station

or fairgrounds remain. But you can zoom all the way in and use Google’s Street

View to at least stroll along Main and see some of the older buildings that might have stood in Anderson’s time (Not likely,

since he lived there from 1884-1896, but still worth a glance.)

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Title Chase: Catch-22

We’ve

all come across certain frustrating situations where you’re “damned if you do,

and damned if you don’t.” Those of us born after the sixties probably came to

know the term “catch-22” long before we were introduced to the book that gave its

own name to these classic no-win situations. Here’s how Joseph Heller described

the self-contradictory bureaucratic blooper that condemned Yossarian to an

endless string of combat missions:

“There was only one catch and that was Catch-22, which specified that a concern for one's safety in the face of dangers that were real and immediate was the process of a rational mind. Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn't, but if he were sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn't have to; but if he didn't want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle.”

But did you know that this circular puzzle was originally known as Catch-18?

Here’s what wikipedia has to say about why it was so hard to land on just the

right title:

“The opening chapter of the novel was originally published in New World Writing as “Catch-18” in 1955, but Heller's agent, Candida Donadio, requested that he change the title of the novel, so it would not be confused with another recently published World War II novel, Leon Uris's Mila 18 . The number 18 has special meaning in Judaism (it means Alive in Gematria) and was relevant to early drafts of the novel which had a somewhat greater Jewish emphasis.

“The title Catch-11 was suggested, with the duplicated 1 paralleling the repetition found in a number of character exchanges in the novel, but because of the release of the 1960 movie Ocean's Eleven, this was also rejected. Catch-17 was rejected so as not to be confused with the World War II film Stalag 17, as was Catch-14 , apparently because the publisher did not feel that 14 was a "funny number." Eventually the title came to be Catch-22 , which, like 11, has a duplicated digit, with the 2 also referring to a number of déjà vu-like events common in the novel.”

I think Catch-22 has a nice ring to it, but come on, calling the

number 14 unfunny? 14 is a hilarious number: the glottal stop right there in

the middle? The only “teen” without an e or an i sound?… Catch-14 would have been

comedy gold.

Monday, January 21, 2013

In the nose with CaptainYossarian

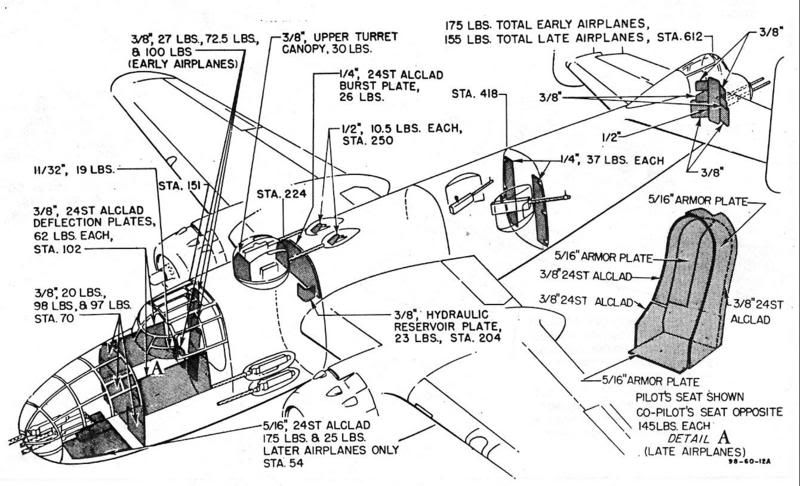

I’m

making my way back through Joseph Heller’s Catch-22

and wanted to get a better handle on the layout of the B-25 bomber that Captain

Yossarian and his squadron fly on an ever-increasing number of combat missions.

Several

times we get references to how Yossarian, as the bombadier in the nose of the

plane, shouts instructions to the pilot and navigator in the cockpit in order

to avoid incoming flack from the anti-aircraft guns below. I couldn’t quite

grasp why the pilot would be blind to this danger, but this picture clarifies

it a bit:

It

also helps you understand why Yossarian wouldn’t be able to squeeze through the tiny passageway into the nose while wearing a parachute (and why he would be so angry with Aarfy after the latter sneaks into the nose behind him to calmly smoke his pipe.) Here are another couple

diagrams showing where the rest of the crew would be stationed, and where poor

Snowden would have been, alone, in the back of the plane.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)