Is it possible that there is one singular moment when an individual ceases to be merely literate, and commences a sojourn much deeper than simple literacy? A moment in time when that person actually becomes a thoughtful, analytical, and persistent reader?

I would assume for many of us that the answer is “No, I became a reader over time.”

For me, the answer is different. Perhaps I am unique, but I can specifically pinpoint the exact moment in time when I consciously made the decision to forego mere literacy in favor of being a well-informed, enlightened, careful, thorough reader of great literature.

In 1998, I was living in the Gracia neighborhood of Barcelona (another story for another day). I was twenty years old. One particular autumn evening, I specifically remember sitting on the subway as it rumbled below La Rambla de Catalunya. I don’t remember where I was going. It was a beautiful evening, to be sure, but I felt bland and uninspired. Across from me on the metro was a girl, probably about my age, and most likely a university student. She probably wore a scarf and a long jacket with a shoulder bag (like most Catalan university girls), although I can’t remember.

What I do remember is sitting there just looking at her as the subway bumped along underground. She was reading.

I remember thinking to myself, “Hmmm, I wonder what she's getting out of that book?”

The book appeared to be a collection of Federico Garcia Lorca poetry. I remember that it had a classic black-and-white photo of the Spanish poet on the cover, and he seemed to be staring at me, and I stared back.

And then I remember thinking, “She’s surely getting more out of that book than I am getting out of my current state of doing nothing.”

And then, “Come to think of it, I see all of these Barcelona university students reading all of the time!”

And then, “Wait a minute! The fact that all of these Barcelona residents enlighten their minds by reading constantly, whereas I do not, seems unjust.”

And then, as I stared at the girl across from me, “But, I too could be reading that book of Lorca poetry in order to similarly enlighten my experience and my mind.”

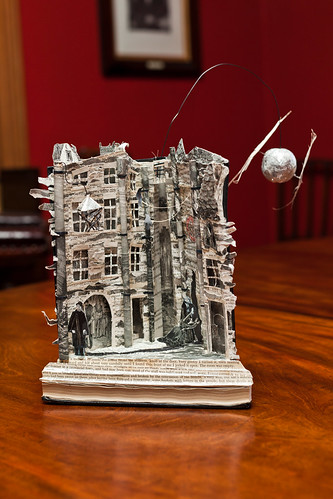

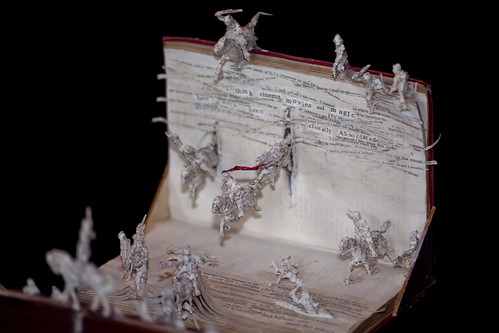

And at that very moment, I became a well-informed, enlightened, careful, thorough reader of literature. I remember it well, as if some forgotten component of my mind just took over from that point. Not long thereafter, I started with Don Quixote de la Mancha (and found that it did enlighten my experience and my mind), and then Dandelion Wine, The Sun Also Rises, A Room With a View, On The Road, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Human Stain, East of Eden, Angle of Repose, The Good Earth, House of Spirits, The Monkey Wrench Gang, Crime And Punishment, One Hundred Years of Solitude, The Chosen, Stones for Ibarra, The Great Gatsby, The Stranger, Herzog, and on and on and on and on and on.

With each novel that I read, I felt a sense of empowerment. I felt that I had been given inside information about the social intricacies of human nature. I felt my mind growing in intelligence. So I kept reading through my college years, and then through law school, and marriage, and young children, and home ownership, and right through an otherwise normal trajectory for a young American male.

Now I read because it’s who I am. And as Ralph Waldo Emerson so aptly stated: “A Man is known by the books he reads.”

But for me, it all began on that autumn evening as I pondered the value that a young Barcelona university student derived from reading poetry on the subway.