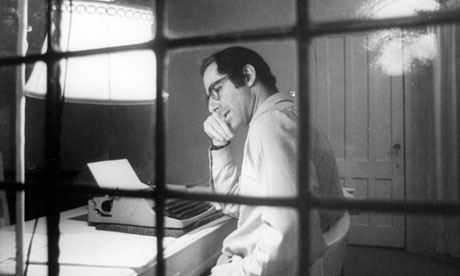

Philip

Roth has been making headlines recently by refusing to publish anything new (he

has officially retired from writing.) But I couldn’t really add my voice to the chorus of voices that are reacting to

that news, because I’d never really read the man. That is, until I picked up Nemesis

a couple of weeks ago. So, what

is my impression of Roth?

In

truth, I don’t feel like my having read his 31st and final novel

gives me too much insight into this perennial Nobel contender. Roth’s got more

prestigious awards than you can shake a stick at, and the only award Nemesis was shortlisted for was the Wellcome Trust

Book Prize, which happens to celebrate medicine in literature (the book

concerns a war-time Polio epidemic.)

But

I was wholly drawn into this story of a young playground director who finds

himself battling the scourge of polio at home, while his best friends fight on

the front lines of World War II. What with

the baseball backdrop, the overhanging shadow of war, and a New York-area Jewish

youth wrestling with religious themes, the book felt like a fitting companion

to Chaim Potok’s The Chosen , a book

I absolutely loved. (Mr. Cantor? Mr. Galanter? Eh? Eh?) But unlike The Chosen , which ends up affirming

religious faith, Nemesis is the account of faith lost.

The

book’s title is never really explained, but since the story unravels like a

classic Greek tragedy, we can only assume that “Nemesis” signifies the Greek

goddess of vengeful retribution, come in the form of the Polio virus. I’ve

spoiled enough of the story as it is, but I’ll just say that Roth breathed

enough life into the time period and

setting to make me want to check out some of his other work. You should, too.

.jpg)

.jpg)