How could the man who penned lines

like these, sound like a character right out of the Andy Griffith show? His

readers may call him William, and his friends may have called him Bill, but

after listening to that folksy, high-pitched twang, I feel like we should all just call him “Pappy.”

Friday, January 25, 2013

The Writer's Voice: Bill "Pappy" Faulkner

Few literary voices are as hard for me to reconcile with the

author’s actual speaking voice as William Faulkner’s.

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Mini Reviews: Pressfield, Barthes and Boyle

Here are some more quick-hit reviews to bring me up to date

on my recent reading:

The

War of Art , by Steven Pressfield

This is a book for anyone who wants to create something

great, or accomplish some secret dream, and has had trouble getting started. “There's

a secret that real writers know that wannabe writers don't and the secret is

this: it's not the writing part that's hard. What's hard is sitting down to

write. What keeps us from sitting down is Resistance.” He does a great job of

naming the condition, and of helping you identify it in your life. And while I

really liked this book as I read it, as I look back after a month or two, I’m

hardpressed to remember what it was exactly that I’m supposed to do about it.

This could just be a fault of mine, but maybe the solutions he provides aren’t

as earth-shattering as the first read led me to believe. I guess I’ll have to

take a second pass through it to make sure I didn’t just fall asleep at the

wheel. But the good news is that it’s a book that would only take a couple

hours to read in the first place. I liked it as a breazy, but well-written,

get-your-butt-in-gear book, but it has yet to change my life so I’m going to

withhold judgement.

Mythologies , by Roland Barthes

This one was at times fascinating, but at other times

bordered on boring and arcane. Barthes is on a mission to uncover the real

meanings behind various pop culture phenomena that interested him in the France

of the mid 1950s. He might deconstruct the Tour de France, analyze a Marlon

Brando movie, pick apart a French governmental policy, explain a recent court

case or take a deep look at celebrity marriages. In some sections I found

myself saying, “Yes, exactly! Why haven’t I ever seen it that way before.” Take

this post I wrote after reading his thoughts on professional wrestling, for

example. But on other topics, I found myself shrugging my shoulders and

wondering, “Who really cares?” I imagine I would have enjoyed the book a lot

more if Barthes and I shared the same cultural milieu, or if he was still

around to turn his attention towards the

American culture of our day. But even so, when he wanders into semiology in the

second part of the book (in essence, the explanation of his explanations) I

quickly lost interest. It’s a pretty interesting literary touchpoint to have,

though, so I’m glad that I read it. And I’ll admit that some parts were

laugh-out-loud funny.

When

the Killing’s Done , by T. Coraghessan

Boyle

Before picking up this book, I had only read two stories by

Boyle, “The Lie” and “ Rapture of the Deep,” both of which were excellent, and

neither of which I can find for free online. So no links, sorry. I was excited

to see what Boyle can do in long form. And while I can’t say the subject matter

of this book was especially gripping (a battle over eradicating invasive

species on the channel islands of California) it really is masterfully written

and it will transport you into the clashing worlds of both environmental

activists and government-employed ecologists. In doing so, Boyle does something

pretty amazing: he makes you care almost equally about the protagonist and the

antagonist, as he unveils the background experiences and rationale that drives

each of them toward collision. I think the narrow focus of the themes keeps it

from being a great, universally appealing book, but it’s certainly a good one.

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

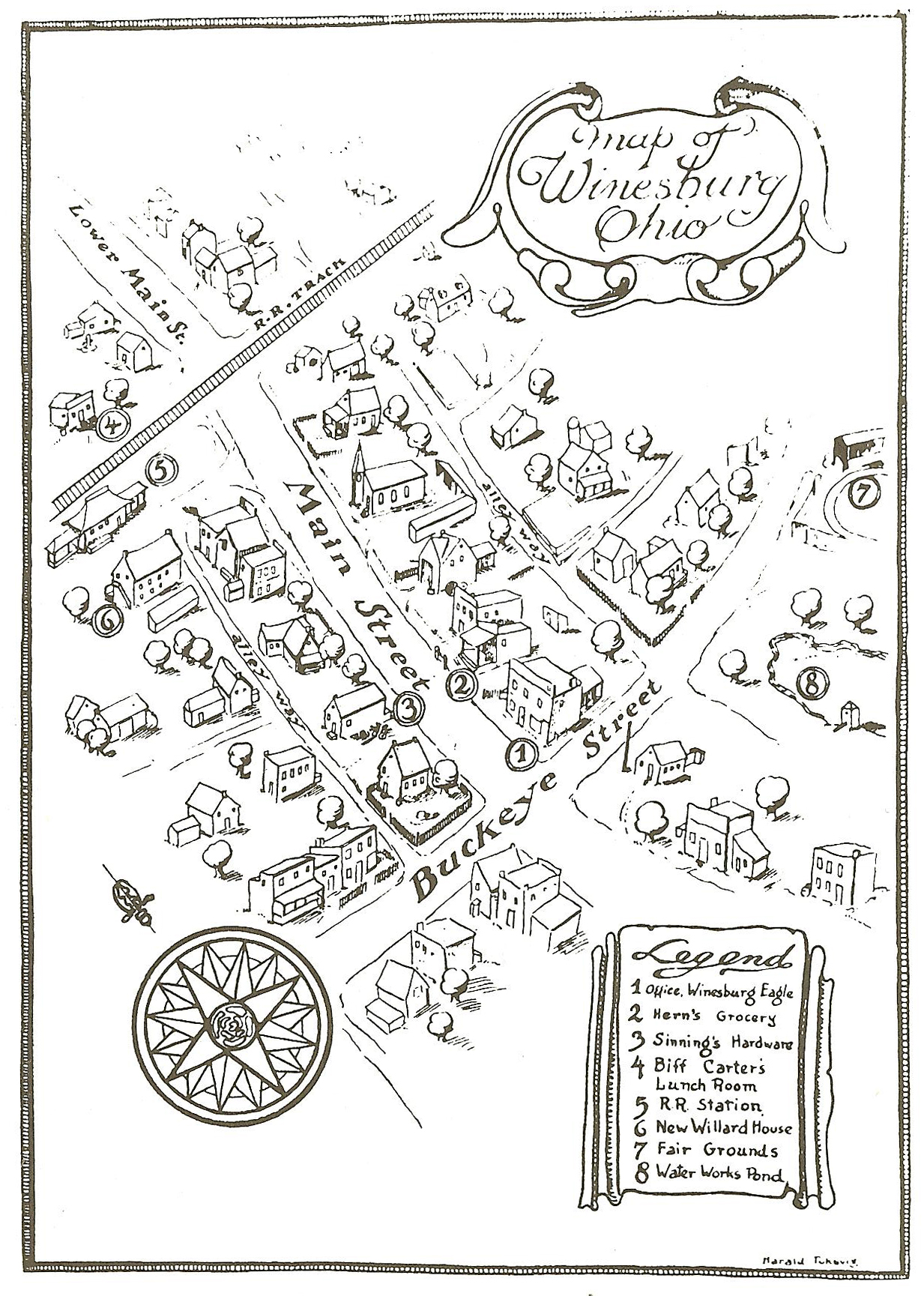

The Real Winesburg, Ohio

Immediately

upon opening the book, readers of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio are greeted

by a hand-drawn map of the fictional town that is the novel’s setting:

Turns

out Winesburg was a thinly veiled representation of Anderson’s own hometown of Clyde,

Ohio which, like its fictional counterpart, has a Main Street that crosses Buckeye

Street and some railroad tracks a little further north. If you’ve read this post

or this post, you know where I’m going with this. Here is what Clyde, OH looks

like today:

The

distances in the map of Winesburg are deceptively short (a half dozen

structures fill the stretch between Buckeye and the Train tracks, a span that

reaches a 1000 feet in the real world) and there’s not much in terms of

landmarks that would jump out and link the two maps. Not even the train station

or fairgrounds remain. But you can zoom all the way in and use Google’s Street

View to at least stroll along Main and see some of the older buildings that might have stood in Anderson’s time (Not likely,

since he lived there from 1884-1896, but still worth a glance.)

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Title Chase: Catch-22

We’ve

all come across certain frustrating situations where you’re “damned if you do,

and damned if you don’t.” Those of us born after the sixties probably came to

know the term “catch-22” long before we were introduced to the book that gave its

own name to these classic no-win situations. Here’s how Joseph Heller described

the self-contradictory bureaucratic blooper that condemned Yossarian to an

endless string of combat missions:

“There was only one catch and that was Catch-22, which specified that a concern for one's safety in the face of dangers that were real and immediate was the process of a rational mind. Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn't, but if he were sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn't have to; but if he didn't want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle.”

But did you know that this circular puzzle was originally known as Catch-18?

Here’s what wikipedia has to say about why it was so hard to land on just the

right title:

“The opening chapter of the novel was originally published in New World Writing as “Catch-18” in 1955, but Heller's agent, Candida Donadio, requested that he change the title of the novel, so it would not be confused with another recently published World War II novel, Leon Uris's Mila 18 . The number 18 has special meaning in Judaism (it means Alive in Gematria) and was relevant to early drafts of the novel which had a somewhat greater Jewish emphasis.

“The title Catch-11 was suggested, with the duplicated 1 paralleling the repetition found in a number of character exchanges in the novel, but because of the release of the 1960 movie Ocean's Eleven, this was also rejected. Catch-17 was rejected so as not to be confused with the World War II film Stalag 17, as was Catch-14 , apparently because the publisher did not feel that 14 was a "funny number." Eventually the title came to be Catch-22 , which, like 11, has a duplicated digit, with the 2 also referring to a number of déjà vu-like events common in the novel.”

I think Catch-22 has a nice ring to it, but come on, calling the

number 14 unfunny? 14 is a hilarious number: the glottal stop right there in

the middle? The only “teen” without an e or an i sound?… Catch-14 would have been

comedy gold.

Monday, January 21, 2013

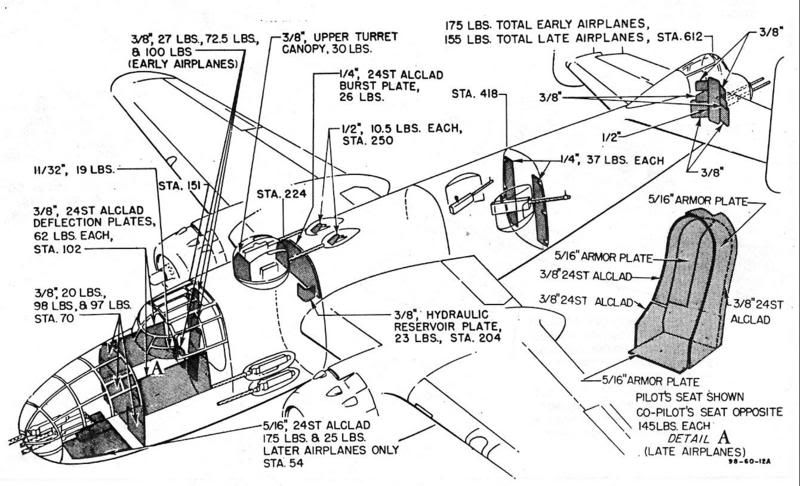

In the nose with CaptainYossarian

I’m

making my way back through Joseph Heller’s Catch-22

and wanted to get a better handle on the layout of the B-25 bomber that Captain

Yossarian and his squadron fly on an ever-increasing number of combat missions.

Several

times we get references to how Yossarian, as the bombadier in the nose of the

plane, shouts instructions to the pilot and navigator in the cockpit in order

to avoid incoming flack from the anti-aircraft guns below. I couldn’t quite

grasp why the pilot would be blind to this danger, but this picture clarifies

it a bit:

It

also helps you understand why Yossarian wouldn’t be able to squeeze through the tiny passageway into the nose while wearing a parachute (and why he would be so angry with Aarfy after the latter sneaks into the nose behind him to calmly smoke his pipe.) Here are another couple

diagrams showing where the rest of the crew would be stationed, and where poor

Snowden would have been, alone, in the back of the plane.

Friday, January 18, 2013

First Line Friday: Stage Directions

Here’s another way to

open your novel: Just start throwing stage directions around. Don’t worry about

giving us a verb- just start naming stuff. Describe things. Give us a flavor for

the stage set.

Take

the opening of Theodore Dreiser’s An

American Tragedy . I read the first three or four “sentences” of this book and

couldn’t find a verb that addresses any of the subjects anywhere .

“Dusk- of a summer night.

“And the tall walls of the commercial heart of an American city of perhaps 400,000 inhabitants- such walls as in time may linger as a mere fable.

“And up the broad street, now comparatively hushed, a little band of six,-a man of about fifty, short, stout, with bushy hair protruding from under a round black felt hat, a most unimportant-looking person, who carried a small portable organ such as is customarily used by street preachers and singers. And with him a awoman perhaps five years his junior, taller, not so broad, but solid….”

It’s

kind of a strange effect. You feel less like a reader than you feel like a

studio executive getting pitched a new movie concept. But it doesn’t have to

describe setting, this kind of opening can just as easily show you what’s

inside the narrator’s brain, like this classic first line from Nabokov’s Lolita :

“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.”

Nabokov’s

done this elsewhere, of course. Here is the opener from Bend Sinister :

“An oblong puddle inset in the coarse asphalt; like a fancy footprint filled to the brim with quicksilver; like a spatulate hole through which you can see the nether sky. Surrounded, I note, by a diffuse tentacled black dampness where some dull dun dead leaves have stuck. Drowned, I should say, before the puddle had shrunk to its present size.”

What do you think? Do stage directions work for you? Or do

you just want the author to get on with the story?

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Author Look-Alikes: Vol. 10

The narrow-set eyes under a straight, low brow hovering over

a long nose and pursed lips… I’d say O Henry bears an undeniable resemblance to

that dude from Parenthood (Sam Jaeger):

And while we’re on the subject of hit tv shows, can anyone

tell me that Mary Shelley doesn’t have a little Lady Edith Crawley in her?

Eyes, nose, lips- it’s almost spooky:

And here’s Ambrose Bierce, who disappeared mysteriously

during the Mexican American War. Perhaps he found the Fountain of Youth that

Ponce de Leon never could, and resurfaced some years later as actor Tom

Skerritt:

Joseph Heller’s wooly coiffure and playfully squinting eyes

conjure up images of a pudgy Art Garfunkel. Like a bridge over troubled water,

he will lay him down:

And doesn’t off-beat children’s author Roald Dahl remind you

just a little bit of that quirky speech pathologist of the late king of England

(Geoffrey Rush)?

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Slovene Literature, Geopolitics and Video Games, oh my!

I’ve been on a Slovene literature kick lately, so it seems

like as good a time as any for a fun fact on the subject:

Did you know, for example, that Assassin’s Creed, one of the

most popular video game franchises in the world, was based on Vladmir Bartol’s novel

Alamut ? No? You didn’t? Well, neither

did I. But here’s why you should care. The book just happens to be the most

widely translated work of Slovenian literature out there, so it’s one of the

rare ones you can pull up online, order quickly and read in English. It’s also a

chillingly prescient story that predicted the Al Quaeda terrorist training

camps that changed the world on 9/11 (and made games like Assassin's Creed "all the rage"), even though it was written clear back in 1938. Here’s the description from Amazon:

Alamut takes place in 11th Century Persia, in the fortress of Alamut, where self-proclaimed prophet Hasan ibn Sabbah is setting up his mad but brilliant plan to rule the region with a handful elite fighters who are to become his "living daggers." By creating a virtual paradise at Alamut, filled with beautiful women, lush gardens, wine and hashish, Sabbah is able to convince his young fighters that they can reach paradise if they follow his commands. With parallels to Osama bin Laden, Alamut tells the story of how Sabbah was able to instill fear into the ruling class by creating a small army of devotees who were willing to kill, and be killed, in order to achieve paradise. Believing in the supreme Ismaili motto “Nothing is true, everything is permitted,” Sabbah wanted to “experiment” with how far he could manipulate religious devotion for his own political gain through appealing to what he called the stupidity and gullibility of people and their passion for pleasure and selfish desires.

I’ve got a copy sitting on my shelf, and this is probably the

year that I tackle it. You should do the same. Check it out:

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

From the pen of Isak Denisen

I’ve

just about got this beautiful book out of my system, but here are a few lines I

highlighted along the way. All emphasis is mine:

"Still, we often talked on the farm of the Safaris that we had been on. Camping places fix themselves in your mind as if you had spent long periods of your life in them. You will remember a curve of your wagon track in the grass on the plain, like the features of a friend.

"Out on the Safaris, I had seen a herd of Buffalo, one hundred and twenty-nine of them, come out of the morning mist under a copper sky, one by one, as if the dark and massive, iron-like animals with the mighty horizontally swung horns were not approaching, but were being created before my eyes and sent out as they were finished. I had seen a herd of Elephant travelling through dense Native forest, where the sunlight is strewn down between the thick creepers in small spots and patches, pacing along as if they had an appointment at the end of the world. It was, in giant size, the border of a very old, infinitely precious Persian carpet, in the dyes of green, yellow and black-brown. I had time after time watched the progression across the plain of the Giraffe, in their queer, inimitable, vegetative gracefulness, as if it were not a herd of animals but a family of rare, long-stemmed, speckled gigantic flowers slowly advancing. I had followed the Rhinos on the morning promenade, when they were sniffing and snorting in the air of the dawn,-which is so cold that it hurts in the nose,- and looked like two very big angular stones rollicking in the long valley and enjoying life together. I had seen the royal lion, before sunrise, below a waning moon, crossing the grey plain on his way home for the kill, drawing a dark wake in the silvery grass, his face still red up to the ears, or during the midday-siesta, when he reposed contentedly in the midst of his family on the short grass and in the delicate, spring-like shade of the broad Acacia trees of his park of Africa."

"A fantastic figure he always was, half of fun and half of diabolism; with a very slight alteration, he might have sat and stared down, on the top of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. He had in him something bright and live; in a painting he would have made a spot of unusually intense colouring; with this he gave a stroke of picturesqueness to my household."

"Here, high above the ground, lived a garrulous restless nation, the little grey monkeys. Where a pack of monkeys had traveled over the road, the smell of them lingered for a long time in the air, a dry and stale, mousy smell."

-from

Isak Denisen’s Out of Africa

Monday, January 14, 2013

Mini Reviews: Morrison, Buck and Dinesen

I have this compulsive

need to make sure I review everything I read last year, but little desire to

sit down and bang out in-depth thoughts of each unreviewed book. So here are a

few quick hits:

Home , by

Toni Morrison

This

was a pretty decent read. Not quite Beloved or Song

of Solomon , but much more engaging than her last book, A Mercy , which I finished, but never

could quite settle into for some reason. This one explores a lot of the

prejudice against, and exploitation of, southern blacks in the Jim Crow era,

but does so without any of the surreal elements of her other novels. She also manages

to avoid casting her characters as simple victims. In particular, there’s a

nice twist to the main character’s recollection of a Korean War episode that

haunts him and that gives the story some depth. I’d recommend it.

Sidenote:

This one was an audio book, read by the author- and while I think I’m generally

in favor of authors reading their own work, this one may have pushed me more

solidly into the “there’s definitely a place for professional voice talent”

camp. Ms. Morrison’s got a somewhat raspy voice that I find soothing, but at 81

years of age, she lacks the breath capacity to read more than 4 or 5 words at a

clip half the time. The result is a Garrison Keillor-esque halt-and-continue

performance that kind of took me out of the book.

The Good Earth , by

Pearl Buck

I had

read this one before, years and years ago, and wanted to see if it would hold

up under the scrutiny of 35-year-old me. It certainly did. I absolutely love

the cyclical nature of the story, of one “great house” replacing another out of

the humblest beginnings, only to be poised at the end of the book to repeat the

mistakes of the past. Some critics claim the novel spreads a litany of

stereotypes about the rural Chinese poor, but the woman spent over 30 years as

a missionary in rural China, I think I’m going to give her the benefit of the

doubt here. If anything, she takes up some pretty universal themes, which is

why people are still reading it 80 years later. It’s a classic. And it made my

top 10 for the year as a re-read. I only wish I could give it more than a

paragraph. I guess there’s this, this and this.

Out of Africa , by

Isak Denisen (Karen Blixen)

Another

of my top 10 reads for the year. I grew up in the 80s, so for me, Out of Africa will always be associated with Meryl Streep

and Robert Redford and Academy Awards. I never had an interest in reading the

book until I came across some praise for it in Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast , where he lauds it as the best book on Africa

he’d ever read. That’s some high praise, indeed. But it’s also highly deserved.

It’s a breathtaking read. If you can get by some of the colonialist views on

race (“All Natives have in them a strong strain of malice, a shrill delight in

things going wrong.” –or- “Until you knew a Native well, it was almost

impossible to get a straight answer from him.”) you will be blown away by the

beautiful prose, all the more impressive because it was written by a native

speaker of Danish. The main thread connecting her fascinating vignettes is an

exploration of African culture and a business story more than anything else-

certainly not the grand love story Hollywood made it out to be. But even if I

didn’t find her story worth my time (I definitely did), this is one of the few

books I would read again simply for the verbal imagery. There’s a reason we

included it in this post. See also this and this.

That’s

enough for today.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)